Civil War Bluejackets: Information School involved in interdisciplinary research using machine learning to shed new light on the ordinary sailors of the American Civil War

“We often try to do multidisciplinary work, but it’s not often you work so closely with people from very different academic backgrounds”, says Dr Morgan Harvey, Senior Lecturer in Data Science at the Information School and Sheffield’s Principal Investigator on the AHRC-funded research project ‘Civil War Bluejackets: Race, Class and Ethnicity in the United States Navy’. Though the Civil War Period of American history - the 1860s - is the context for this project, Dr Harvey says “it’s actually pretty much exactly a clean 50/50 split between the historical part of the project and the information science part.”

Along with Postdoctoral Researcher Dr Adam Funk in Sheffield and former Sheffield colleague Professor Frank Hopfgartner of the University of Koblenz-Landau in Germany, Dr Harvey is collaborating with historians Professor David Gleeson and Dr Damien Shiels at Northumbria University. Gleeson and Harvey lead the project as co-PIs, and the team is completed by Associate Professor Wayne Hsieh of the United States Naval Academy. The project is just under one year into its three year duration.

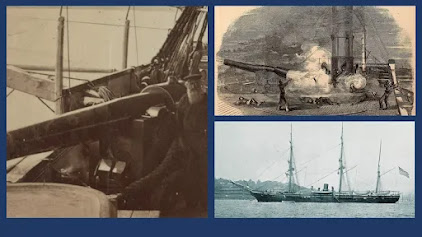

The focus of the project is the hundreds of thousands of muster rolls released by the US Naval Academy Museum, documenting sailors and officers - known as ‘Bluejackets’ because of their blue uniforms - who were aboard Union vessels during the American Civil War. These rolls - essentially registers of every crew member aboard a given ship - would be taken on a regular basis, and are surprisingly detailed, including such details as when and where a sailor was born, their eye colour, hair colour, skin complexion, tattoos and previous occupations.

x

The project is split into four strands, one of which is ‘Machine Learning’. This is the domain of the team at the Information School in Sheffield, and their first task is digitising these paper records, which is no small undertaking.

“They’re written in mid-19th Century American hand, and they weren’t always very precise”, says Dr Harvey of the difficulties working with such old, handwritten documents. “These people weren’t creating records with the idea that 160 years later someone would be trying to do something useful with them!”

Using crowd volunteering platform Zooniverse, the team are recruiting volunteers on a rolling basis to get through the initial stages of this transcription process. The volunteers manually transcribe one column at a time from a photo of a specific muster sheet, drawing a box on the photo around the text they’ve transcribed. A minimum of five people look at each sheet, to account for inevitable discrepancies between what different people read in the handwriting. More than 650 volunteers have been recruited so far, but the team are aiming for thousands, with Dr Harvey and Dr Funk also getting involved themselves.

You can volunteer to assist with the transcription yourself here.

Dr Funk has developed a piece of software that creates an image file of the box that each volunteer has drawn around the text they’ve transcribed, along with the transcription itself and which column it’s from. These images will be fed into a deep learning model, which is being developed as part of the project, to automate a large part of the transcription once the manual transcriptions have generated enough data to train the model.

“We think that the optical character recognition software we’re developing will do better at recognising things like age and height, where it’s just expecting numbers, than things like names”, says Dr Funk. “The joined-up handwriting is often very loopy, and letters sometimes run into the next row below them on the form.” Lots of the enlisted naval men will have been illiterate, too, meaning they don’t spell their name consistently across different muster rolls, plus the recording officers may have differing interpretations of the name given to them verbally. There’s also the issue of choppy seas making handwriting even less legible than it would have been on land. The machine learning model will be trained separately on each column to try and account for these kinds of issues, and some probability theory will be applied for columns such as ‘place of recruitment’, where the text should refer to only one of a few options.

After the transcription process is where the historical aspect of the project begins. The aim is to identify individuals and link them between multiple records. This will allow the team to see if a given person has moved around between vessels over the course of the war, but also to link them to entries in other databases from the period, such as recruitment records, pension records and hospital records.

“Many of these records are the first time that emancipated, previously enslaved people have been recorded as individuals, rather than chattels of a white slave owner, so its quite significant”

“The idea is to generate a searchable, transcribed list of every individual in every US naval vessel during the Civil War and link those to other digital records”, explains Dr Harvey. This will allow historians to write histories of common sailors, looking at things like race, ethnicity and class.

“Many of these records are the first time that emancipated, previously enslaved people have been recorded as individuals, rather than chattels of a white slave owner, so its quite significant”, says Dr Harvey. Roughly 30% of the US sailors were from the UK and Ireland - which was illegal then, as it is now - so there’s a local interest, too. Additionally, most historical records focus on higher ranking officers, rather than the working class enlisted men, so this project should help address the issue of underrepresentation of these people.

Thanks to the data science and machine learning groundwork of the project being laid here in Sheffield, historians will be able to do this kind of analysis en-masse.

“Typically, when historians do this kind of work, they might pick a few people and try and trace them through the different records”, explains Dr Harvey. “This project will allow them to look at the progression through time of tens of thousands of people and really look at demographics in a way that they couldn’t before.”

Though the linking of individuals in the records uses more established data science methods than the transcription, and will be using standard ASCII text rather than 19th century handwriting, it’s still not a wholly straightforward task.

“This would be much easier these days, as everyone has a National Insurance number or Social Security number”, says Dr Harvey of the challenges. “No such things existed during the Civil War period, so it’ll be harder to uniquely identify people. I suppose that’s a good thing, though, otherwise there wouldn’t be a project!” There are other issues with incomplete records, where an officer was clearly in a rush and skipped some columns. It’s also very hard to find consistency in columns like complexion or skin colour; words like “florid” and “swarthy” are used, as well as some distasteful and offensive words we’d never use today, none of which are applied uniformly.

Aside from the machine learning strand to the project covered in Sheffield, there are three specific strands being looked at by the historians in Northumberland. One is about race and ethnicity; what was the makeup of the sailor population, and how did it change? African-American sailors only appear in the last few years of the Civil War, after the emancipation of slaves, for example.

Another strand looks at class; the occupational background of sailors, and how this related to their place of origin, their race, and the rankings on the ship. Said ship ranks are much more specific on these muster rolls than they are on modern vessels, with some ranks describing exactly what a person did, such as ‘Coal Hauler’, or others like ‘Landsman’ simply describing someone with no sea experience.

“There are some sailors whose ranks are just listed as ‘Boy’!”, says Dr Funk.

“There’s also ‘Senior Boy’!”, adds Dr Harvey.

The final strand of the project is ‘transnational’; how much did the US Navy rely on foreign-born people, such as those from the UK and Ireland? We know even less about other European countries, or other British colonies like Canada and countries in the Caribbean. How did US naval recruitment from these places compare to recruitment to those countries’ own navies? Some recruits would enlist to take advantage of a bounty payment which was offered to boost numbers, and then desert the navy to enlist elsewhere for another payment. One reason why the muster rolls were so detailed, including things like tattoos, was to try and identify people and stop this happening.

“How they could do that with this record system I’m not sure!”, says Dr Funk.

“For someone with a background in information and data science, the seeming lack of thought that’s been put into designing these records is quite amazing!”, says Dr Harvey. “You just wouldn’t design things like this if you ever planned to use them to look things up. It does make it quite fun, though!”

The project came about through Dr Harvey’s previous employment at Northumbria University. Once Harvey moved to Sheffield, Gleeson contacted him to ask if he was interested in a project about the American Civil War - a proposal for which he was fortuitously primed as a child.

“Serendipitously, for whatever reason, my Dad has a strong interest in the Civil War”, Dr Harvey explains. “I must be one of the few British people who had seen the film Gettysburg and its sequel Gods and Generals by about the age of 10 - both of which are incredibly long!”

“Collaboration between historians and data scientists or machine learning experts is very rare. It’s pretty novel to be applying these kinds of methods to this kind of data.”

Dr Funk’s interest in the project is close to home in a different way.

“I’m from Virginia, which is where many Civil War battlefields are”, he says. “The famous Battle of Hampton Roads took place in the James River estuary in Virginia.”

Though there is some precedent for using machine learning in research on old, handwritten text (such as George III’s writings), Dr Harvey believes that this project is still quite unusual.

“Collaboration between historians and data scientists or machine learning experts is very rare”, he says. “It’s pretty novel to be applying these kinds of methods to this kind of data.”

Dr Harvey also talks about having to explain concepts to his historian colleagues that he never has to explain in the information- and data-focused world of his job as an academic at the Information School - another interesting aspect of a project this interdisciplinary.

“In a way, you could call this a Digital Humanities project”, adds Dr Funk. “In literature research, they use Machine Learning to do author identification in a corpus of texts, and they find that you can get similar results to those that humanities scholars would get through traditional methods, but they can do it efficiently at a large scale. That’s what we’re trying to achieve with this project, too.”

The research team are planning three historical publications and a monograph as the outputs of the project. The Civil War Sailor Internet Resource - the name for the searchable database of records mentioned earlier - will be open access, available to anyone at the end of the project. This will be launched with a conference at the US Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, tying into US Black History Month in February 2025. There will be a second public launch at Howard University in Washington DC - a historically black university with origins in the Civil War. Finally, a launch in Northumbria will highlight the British angle to the project.

The other databases to which the records on the Civil War Sailor Internet Resource will link may not be free, but most are owned by ancestry.com, to which most historians and genealogy enthusiasts have access already. With genealogy being such a huge interest these days, the potential reach of this project’s results is vast.

“For many African American people in particular, if they look back into their genealogy, at a certain point the records just stop”, says Dr Harvey. “If we can push those records back even a little bit further then that’s a great contribution.”

There’s also a surprising amount of interest in the American Civil War in the UK.

“A few years ago I went to a festival at Norfolk Heritage Park in Sheffield”, says Dr Funk. “There was an American Civil War reenactment society there that was big enough that they had a cannon to fire!”

There are so many interesting individual stories emerging from these thousands of muster records that the team have set up a Twitter account highlighting them as they are discovered. Dr Harvey and Dr Funk continue to find interesting items themselves, too.

“Morgan and I would have been the tallest people on any of the ships we’ve looked at so far!”, says Dr Funk. “The heights we’ve seen tend to be in the 5” to 5”10’ range”.

By applying machine learning techniques to a vast set of historical data and working across humanities and social sciences, the Bluejackets project will deliver meaningful, usable data for use not only by the historians on the project itself but any number of future researchers and amateur historians. With detailed information on race, class and other such demographics, the possibilities for future findings in these important and impactful domains using this data are extensive, and this project is a testament to the value of truly interdisciplinary research.

- Richard Spencer

Comments